Marcel Duchamp's Fountain

Introduction

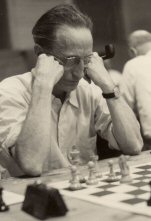

Marcel Duchamp was an artist at the very center of the Dada art movement, both

in France and in New York. At the time many Dada artists were using “found

objects” to make pieces they called a “ready-made” sculpture. The artist chose

an object that was mass-produced and gave it the title of art, therefore forcing

people to look at it in new light. Perhaps the most famous and controversial of

these pieces is Duchamp’s Fountain. Marcel Duchamp was an artist at the very center of the Dada art movement, both

in France and in New York. At the time many Dada artists were using “found

objects” to make pieces they called a “ready-made” sculpture. The artist chose

an object that was mass-produced and gave it the title of art, therefore forcing

people to look at it in new light. Perhaps the most famous and controversial of

these pieces is Duchamp’s Fountain. Fountain is a mass-produced white

porcelain urinal that was exhibited laying on its back. It has the “artist’s”

signature, R. Mutt and date, 1917, scribbled in black ink on the side. There are

no inherent aesthetic qualities to this piece, the “art” of it was in the

choosing and forcing the viewers to think of it as something other than a

urinal. The “artist’s” signature was a play on the Mott plumbing company and a

popular comic during the time named Mutt and Jeff.

Creation of The Fountain

Duchamp helped to found the Society of Independent Artists in New York. They put

on an exhibition in 1917, in which anyone could enter any piece of art as long

as they paid the six-dollar entry fee. There was supposedly no judging and no

restrictions. This situation is what sparked Duchamp into making Fountain. He

wanted to test just how free these artists could be. Of course the committee

refused to hang the piece. Duchamp wrote a letter defending the piece published

in The Blind Man, a small magazine he worked at as an editor. He wrote, “Whether

Mr. Mutt with his own hands made the fountain or not has no importance. He CHOSE

it. He took an ordinary article of life, placed it so it’s useful significance

disappeared under a new title and point of view - (he) created a new thought for

that object” (Time-Life Library of Art, 39). This was exactly what the point of

ready-made art was, so how could the Society of Independent Artists deny it for

the show; he wanted to know. The committee said it failed to meet their moral

standards which Duchamp countered was ridiculous. The urinal was an item one

would see every day in plumber's show windows.

The Dada Movement

Duchamp was part of a major movement in the art industry called Dadaism as a

means of rebellion against the war. The major participants gathered together in

neutral Switzerland where they formed the Cabaret Voltaire, a place to discuss

and share art and to prove that “these humiliating times have not succeeded in

wresting respect from us” (TMLA, 56). They took up the word dada which is a

French word children used meaning hobby-horse, because it expressed the

primitive nature and newness of their art.

These artists described Dadaism as being against the future, and stated that

art was not serious. It was a revolutionary movement for them, they treated it

as a violent assault on the accepted values. The Dadaists looked up to the

Cubists and Futurists and said that art should no longer be viewed simply as

reality interpretation, but instead as a piece of reality itself. The Dada

movement based on articles in several small magazines touted the cause of

anti-art, was ran by some of the most famous names in art history such as

photographer Alfred Stieglitz. These magazines often defied all conventional

rules of design and good taste according to the publishing world.

Anti-Art

The Dadaists exclaimed that they despised what was commonly regarded as art, and

instead “put the whole universe on the lofty throne of art.” (TLLA, 58) This was

where Duchamp’s ready-made pieces came heavily into play. Although Duchamp was

mostly unaware of this movement taking places thousands of miles away, he

maintained a conspicuous undermining of high art through his publications in New

York and his artwork which had a lot of the elements of the Dada movement in

them. These elements consisted of a lack of realism, an opposition to the

accepted ideas of fine art and expressions of confusion and eccentricity. The Dadaists exclaimed that they despised what was commonly regarded as art, and

instead “put the whole universe on the lofty throne of art.” (TLLA, 58) This was

where Duchamp’s ready-made pieces came heavily into play. Although Duchamp was

mostly unaware of this movement taking places thousands of miles away, he

maintained a conspicuous undermining of high art through his publications in New

York and his artwork which had a lot of the elements of the Dada movement in

them. These elements consisted of a lack of realism, an opposition to the

accepted ideas of fine art and expressions of confusion and eccentricity.

In 1920, the Dada movement relocated to Paris, France. Here they began by

staging readings at the Palais des Fetes. The anti-war Dada movement was being

simultaneously attacked by the press and lauded by prominent intellectuals. The

Dadaists, pleased with this separation from the art world they were rebelling

against, found formal artists beginning to sever any ties with them. This is

when Duchamp unveiled his latest ready-made work. It was a copy of the Mona Lisa

on which he added a mustache and goatee. Years later he signed an unaltered

print and called it Rasee, the French word for shaved.

Shortly after this unveiling, Duchamp returned to New York. He never attended

any of the Dadaists demonstrations which added to his reputation among the

movement. So much that at the Galerie Montaigne, the organizers wired Duchamp in

New York asking for some of his works be included in the show. He wrote back

declining, with a vulgar pun, and they instead hung his telegram. These

demonstrations often ended in food being thrown or real violence, and the crowd

began to enjoy themselves. This did not please the Dadaists, as they were trying

to represent an antithesis of culture and enjoyment. Shortly afterwards the Dada

movement collapsed. One of its main supporters, André Breton, withdrew from the

cause stating that it “had been merely a state of mind which served to keep us

in a state of readiness - from which we shall now start out, in all lucidity,

toward that which calls us” (TLLA, 63).

Conclusion

Marcel Duchamp was one of the movements few artists who would carry the

implications of Dadaism to its logical conclusion (TLLA, 65). He thought of

Dadaism as a sort of nihilism, a way to avoid being influenced by the past or

one’s surroundings and break free from conventions. Dada went on to inspire

Surrealism, Abstract, Expressionism, and Pop Art and Duchamp’s ready-made pieces

and painted works such as Nude Descending a Staircase No.2 were the precursors

to these more popular and famous movements. Marcel Duchamp was one of the movements few artists who would carry the

implications of Dadaism to its logical conclusion (TLLA, 65). He thought of

Dadaism as a sort of nihilism, a way to avoid being influenced by the past or

one’s surroundings and break free from conventions. Dada went on to inspire

Surrealism, Abstract, Expressionism, and Pop Art and Duchamp’s ready-made pieces

and painted works such as Nude Descending a Staircase No.2 were the precursors

to these more popular and famous movements.

Fountain, his first ready-made piece was and still is one of the most famous

works of art to come out of and represent the Dadaist movement. It perfectly

represented a break from art’s historical roots and forced the observers to

break away from the logical and mainstream way of looking at objects and art.

Works Cited

Tomkins, Calvin. Time Life Library of Art. The World of Marcel Duchamp.

Alexandria, Virginia: Time Life Books Inc., 1977. Print.

Kleiner, Fred S. Gardner’s Art Through the Ages 13th Edition Volume 2. Boston,

MA: Thomson Higher Education, 2009. Print.

Art

Graffiti Artists and Radical Media

Marcel Duchamp's Fountain

The Genius of

Jan Van Eyck |