The Fall of Tsarist Russia

Overview

Tsarism in Russia, developed throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, and was

characterized by a single leader’s despotic rule over the entire population. The

Tsar was a ruler who had absolute control over all issues. He was the final

authority on all matters, including the religious, and delegated power only to

those who would make decisions and carry out orders according to his wishes.

Tsarism was extremely popular among the majority of Russian individuals for many

years, and it was the members of the aristocracy, instead, who were blamed by

the public for Russia’s economic crisis.

The breakdown of this system was the result of many tensions that built up

over centuries and escalated in the final years of the autocratic government

system. Russia’s strict social hierarchy distinguished and ostracized the

working classes from the opulent aristocratic landowners that presided over them

and thus, produced a mass of impecunious individuals who had no means of

recovering from their penury. In order to preserve his volatile position as Tsar

Alexander II attempted minor reforms to the nation’s economy, social system as

well as the governmental structure. Despite the numerous improvements initiated

by Alexander II (such as the emancipation of the serfs in 1961), he was

assassinated and his son, Alexander III, assumed the role of Tsar as his

successor. The new tsar, Alexander III, was extremely reserved and disliked some

of the liberal decisions made by his father. Throughout his reign, he fought no

wars and was subsequently labeled “ The Peace-maker”. After his death in 1894,

his son Nicholas II ascended the throne of Russia as the final tsar of Russia.

The economic strain and the lack of support of the illiberal and monocratic

Tsarist regime led to many insurrectionist notions arising from the peasant and

urban working classes. This therefore contributed to the almost inexorable

downfall of the Tsar. The public discontent with both the employment, and living

conditions of the working class, as they endeavored to survive extreme poverty,

gave rise to many revolutionary ideas and led to subsequent rebellion.

The Tsars

Tsarist Russia was the only true autocracy remaining in Europe, during the time

just before the revolutions. The Tsar believed he had been chosen by God and was

not required to hold elections nor listen or heed the reeds or opinions of his

“subjects”.

Tsar Alexander II

|

Tsar Alexander II:

|

Despite the conventions of society and the severity of the political

despotism, Tsar Alexander II, under the pretense of altruism, approved many

reforms to improve the nation’s political, economical and social needs.

Alexander II desired some amelioration and positive reformation in order to

stabilize the nation’s unrest and, in 1861, he announced the passing of an

“Emancipation Manifesto” which suggested 17 judicial acts that would liberate

the Russian serfs. He declared that the maintaining of private serfs would be

prohibited and that all serfs would be permitted to purchase land from their

proprietors. In addition to this, Alexander introduced various local government

reforms in 1864, which were called a Zemstva. This Zemstva provided each district

with a council that possessed the authority to construct roads and schools and

supply medical services. The Tsar reformed the military, the previously

prevalent social hierarchy as well as both the political and educational

systems. Alexander’s focal motivations in modernizing the nation was to ensure

the preservation of the Tsarist autocracy but, as his reforms were not radical

enough, he was eventually assassinated by a fanatical insurrectionist group

entitled “People’s Will” on March 1, 1881; he was succeeded by his son Alexander

III. Thus, the reign of Alexander II provided the country with a renewed power

and prominence and is therefore a significant contribution to the strengths of

the Tsarist regime.

Tsar Alexander III

In juxtaposition to his father’s reformist notions, the reign of Alexander III

marked a period of political and social repression in Russia as a reaction to

the witnessing of his father’s murder. Alexander III empowered and reorganized

the nation’s secret police into the severe and brutal Okhrana and positioned it

under the Ministry of Internal Affairs. This particular political office limited

the power of the Zemstva and the legislative power of the governing body, the

Duma. In order to protect the nation from what he considered to be the

detrimental impact of modernism, Alexander III placed strict value on the

oppression of all heterodox religions and non-Russian individuals. He also

repressed all forms of autonomy and extensively promoted anti-Semitism.

Alexander instated a policy of Russification in which all inhabitants of the nation,

regardless of their background, were expected to adhere to the conventions of

Russian society and begin to speak and act Russian. In blatant opposition to the

Tsar’s demands, many radical underground political organizations and movements

continued to develop. Alexander III died from liver disease on October 20, 1894

and was succeeded by his eldest son, Nicholas II. The severe repression that was

prevalent during the autarchy of Alexander III therefore increased the flaws

that were existent within the Russian Tsarist system. In juxtaposition to his father’s reformist notions, the reign of Alexander III

marked a period of political and social repression in Russia as a reaction to

the witnessing of his father’s murder. Alexander III empowered and reorganized

the nation’s secret police into the severe and brutal Okhrana and positioned it

under the Ministry of Internal Affairs. This particular political office limited

the power of the Zemstva and the legislative power of the governing body, the

Duma. In order to protect the nation from what he considered to be the

detrimental impact of modernism, Alexander III placed strict value on the

oppression of all heterodox religions and non-Russian individuals. He also

repressed all forms of autonomy and extensively promoted anti-Semitism.

Alexander instated a policy of Russification in which all inhabitants of the nation,

regardless of their background, were expected to adhere to the conventions of

Russian society and begin to speak and act Russian. In blatant opposition to the

Tsar’s demands, many radical underground political organizations and movements

continued to develop. Alexander III died from liver disease on October 20, 1894

and was succeeded by his eldest son, Nicholas II. The severe repression that was

prevalent during the autarchy of Alexander III therefore increased the flaws

that were existent within the Russian Tsarist system.

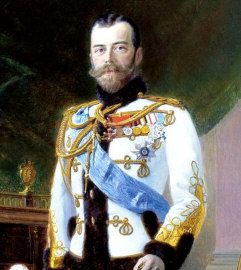

Effects of Nicholas II’s Poor Leadership on the Collapse of the Tsarist

Regime

The autocratic reign of Tsar Nicholas II caused dissatisfaction within society

and feasibly provided numerous motives for the lower and working class Russians

to yearn for a more egalitarian political structure. Nicholas II was married to

Alexandra, a German princess who was the grand-daughter of Queen Victoria. She

was a traditionalist and an indefatigable defender of totalitarianism who

entreated her husband to defy all demands for governmental amelioration. Due to

his belief that a small victorious war would subdue the nation’s political

unrest as well as his desire to expand the Russian empire, Nicholas attacked the

Japanese empire. The Japanese eventually defeated Nicholas’ military reducing

the reputation of the Tsarist regime and sparking a number of reactionary groups

to evolve. Alexander’s unwillingness to modernize Russia and his attempts to

repress all seditious groups contributed to the many weaknesses of the Tsarist

system and ultimately led to the Russian Revolution that occurred later, in

1917. The autocratic reign of Tsar Nicholas II caused dissatisfaction within society

and feasibly provided numerous motives for the lower and working class Russians

to yearn for a more egalitarian political structure. Nicholas II was married to

Alexandra, a German princess who was the grand-daughter of Queen Victoria. She

was a traditionalist and an indefatigable defender of totalitarianism who

entreated her husband to defy all demands for governmental amelioration. Due to

his belief that a small victorious war would subdue the nation’s political

unrest as well as his desire to expand the Russian empire, Nicholas attacked the

Japanese empire. The Japanese eventually defeated Nicholas’ military reducing

the reputation of the Tsarist regime and sparking a number of reactionary groups

to evolve. Alexander’s unwillingness to modernize Russia and his attempts to

repress all seditious groups contributed to the many weaknesses of the Tsarist

system and ultimately led to the Russian Revolution that occurred later, in

1917.

The aristocracy, the traditional supporters of the Tsarist regime, began to

lose respect for the Tsar. Nicholas II’s ineptitude to govern the nation was

revealed in his association with Rasputin (an alleged “mystic” and the adviser

to Nicholas, who was unpopular with the public) as well as his violent decisions

concerning the nature of the suppression of the social unrest on Bloody Sunday

(January 1905) where soldiers fired at random into a crowd of peaceful

protesters. This display of poor leadership caused approximately 92 deaths and

resulted in the wounding of over one hundred people. Another demonstration of

defective leadership was his decision to disband the constitutional government

after the 1905 Revolution. The intelligentsia began to maintain that they could

no longer depend on the Tsar to heed their requirements and interests. The

realization of his inadequacy and the discontentment of the influential social

classes with the nation’s politics, was instrumental in creating the ultimate

doom of the Tsarist system.

In these ways, Nicholas’ reign as Tsar was doomed to a climacteric extent by

1914 due to social, economic and military reasons. The recognition of his

inadequacy to rule by the entirety of society and the loss of respect for him by

the influential classes significantly contributed to the eradication of the

dictatorial regime. Additionally, the appalling living and working conditions of

the urban workers as well as the penury of the peasantry ultimately resulted in

the formation of revolutionary groups that opposed the authoritarianism of the

Tsar. Further, despite the economic and agrarian reforms initiated by Witte and

Stolypin, WWI forced Russia into an economic recession with harsh food

shortages, social unrest and economic tension that eventually generated the

downfall of the Tsar’s draconian rule.

Impact of Socio-economic Antagonism on the Collapse of Tsarist Rule

There was not enough fertile land to meet the demands of Russia’s growing

population. The majority of Russian land was inapposite for farming. During the

Tsarist rule, Russia was a predominantly agrarian nation and therefore, its lack

of adequate farming land was a significant strain on the economy. Russia was

extremely underdeveloped, using inefficient agriculture methods and were far

behind Britain, who had already undergone agricultural revolution a century

before. In a similar way, Russia was falling further behind other western

nations in terms of industry. It was in desperate need of industrialization and

modernization in order to gain more economic stability, generate the military

resources required to maintain Russia’s position as a major world power and

create employment for the surplus rural population. This, however, was

unfeasible with Russia’s flawed system of government. There was not enough fertile land to meet the demands of Russia’s growing

population. The majority of Russian land was inapposite for farming. During the

Tsarist rule, Russia was a predominantly agrarian nation and therefore, its lack

of adequate farming land was a significant strain on the economy. Russia was

extremely underdeveloped, using inefficient agriculture methods and were far

behind Britain, who had already undergone agricultural revolution a century

before. In a similar way, Russia was falling further behind other western

nations in terms of industry. It was in desperate need of industrialization and

modernization in order to gain more economic stability, generate the military

resources required to maintain Russia’s position as a major world power and

create employment for the surplus rural population. This, however, was

unfeasible with Russia’s flawed system of government.

The Effects of Russia’s Social Hierarchy on the Failure of Autocratic Rule

The uncompromising feudal system that was existent within Tsarist Russia was a

significant flaw that contributed to the many failings of the dictatorial

regime. Russia was governed by a single autocratic ruler who distributed power

among individuals of the aristocracy. Tsars would employ these landed patricians

to supervise the enforcement of laws and would also utilize the military to

forcefully subdue any rebellions or discontent with the totalitarian political

system. The aristocracy controlled approximately 50% of the nation’s capital but

was comprised of only 1% of the country’s population who dominated prominent

positions within the military and government. The other classes within the

system were excluded from politics due to their social status and lack of

education.

Additionally, the bourgeoisie were small in number and, despite their

relative affluence and standard of living, they had no influence on the nation’s

government. Many were dissatisfied with their exclusion from affairs of state

and, thus, sought after a more progressive and liberal Russia. In conjunction

with this, the urban workers made up about 10% of the Russian population. They

were moderately educated and were concentrated in the larger, more industrial

cities where they were influenced by many radical, insurrectionist notions of an

egalitarian society. The serfs or peasantry were subsistence farmers and

comprised over 80% of the nation’s population. They had egregious living and

working conditions and were over-taxed at an rate which made it virtually

impossible to pay taxes.

The strict hierarchical structure caused a significant amount of unrest

within the lower, repressed classes whose autonomy and political rights were

unrecognized. The preponderance of the Russian populace were dissatisfied with

their exclusion from affairs of state and, thus, sought after a more progressive

and liberal Russia. The primitive feudalistic system that subsisted within

Tsarist Russia was therefore a crucial foible that was instrumental in adding to

the abundant imperfections of the oppressive dictatorial system of government.

Effects of the economic strain caused by WWI

The social and economic tension originating from the first World War caused the

downfall of the Tsar to a momentous extent. The socially unpopular war revealed

the egotism and expertness of the upper echelons of society as well as the

amoral military leadership. The incompetent training of the soldiers resulted in

substandard leadership and a military that was unprepared for modern warfare.

The war also produced mass food shortages, economic strain and formal social

recognition of the inadequacy of the Tsar and the military leadership. The

result of this, as well as the loss of morale that occurred due to a monumental

defeat by Germany in the Battle of Tannenberg in August 1914. The social and economic tension originating from the first World War caused the

downfall of the Tsar to a momentous extent. The socially unpopular war revealed

the egotism and expertness of the upper echelons of society as well as the

amoral military leadership. The incompetent training of the soldiers resulted in

substandard leadership and a military that was unprepared for modern warfare.

The war also produced mass food shortages, economic strain and formal social

recognition of the inadequacy of the Tsar and the military leadership. The

result of this, as well as the loss of morale that occurred due to a monumental

defeat by Germany in the Battle of Tannenberg in August 1914.

Reforms of Stolypin and Witte

Alternatively, the reforms of Pyotr Stolypin and Sergei Witte could

potentially have preserved Nicholas’ autarchic regime until their replacement by a

series of nonentities whose single policy was that of repression.

Sergei Witte was the Finance Minister from 1892 until 1903. Witte’s

objective, to maintain the existing Tsarist despotism, was attempted to be

reached by means of modernization. He desired to modernize the Russian economy

to equal the degree of industrialization of the Western nations. In order to

achieve this, he invited many foreign, skilled workers to Russia to advance the

entirety of its financial, social and military systems. Witte also initiated the

extension of the railways and directed the construction of the prominent

Trans-Siberian Railway. Despite these positive reforms, Witte’s policies relied

heavily on foreign loans and investments and did not heed the agrarian needs of

the peasantry. This ephemeral higher standard of living created by Witte’s

advancements as well as the period of brief economic boom eventually resulted in

a recession which caused significant dissatisfaction within the urban working

class. Further, the worldwide economic crisis meant that there was no market for

Russian industrial goods and led to further unemployment. Following this, the

poor harvests in 1900 and 1902 caused extreme dissatisfaction amongst the

workers. Sergei Witte was the Finance Minister from 1892 until 1903. Witte’s

objective, to maintain the existing Tsarist despotism, was attempted to be

reached by means of modernization. He desired to modernize the Russian economy

to equal the degree of industrialization of the Western nations. In order to

achieve this, he invited many foreign, skilled workers to Russia to advance the

entirety of its financial, social and military systems. Witte also initiated the

extension of the railways and directed the construction of the prominent

Trans-Siberian Railway. Despite these positive reforms, Witte’s policies relied

heavily on foreign loans and investments and did not heed the agrarian needs of

the peasantry. This ephemeral higher standard of living created by Witte’s

advancements as well as the period of brief economic boom eventually resulted in

a recession which caused significant dissatisfaction within the urban working

class. Further, the worldwide economic crisis meant that there was no market for

Russian industrial goods and led to further unemployment. Following this, the

poor harvests in 1900 and 1902 caused extreme dissatisfaction amongst the

workers.

Pyotr Stolypin was made Prime Minister by Tsar Nicholas II in 1906. He held

the belief that action needed to be taken in order to stabilize Tsarism, in the

years subsequent to the 1905 revolution. He desired to provide universal

education in Russia by 1922 and to clamp down on insurrectionists. In 1906, 21,000 individuals were exiled and 1008 were executed by hanging;

the noose began to be referred to as “Stolypin’s necktie.” Stolypin’s reforms included the

introduction of a Duma, a legislative body elected by a select group of

individuals and the modernization of agriculture by dissolving the mir system of

farming and passing land from communal holding to individual possession. He was

assassinated by a Social Revolutionary in 1911, therefore eliminating the last

probable savior of the Tsarist system.

Although some reforms and rulers that were in place during the Tsarist regime

in Russia were positive, many had a detrimental impact upon Russian society,

economy and eventually, the Tsars themselves. The flaws that were prevalent

within the Tsars’ system of despotism were the origin of the disintegration of

the existing social structure, the widespread discontent with the system of

government and the declining economy of the nation. The severe feudalistic

hierarchy, the penury of the serfs and lower classes and the social and

political repression strongly overpower the minor reforms instituted by

Alexander II and led to the ultimate downfall of Tsarism in Russia.

Politics

The Fall of Tsarist Russia |